As someone who has had the privilege to sit ringside for a number of fights (largely thanks to TQBR), I can attest that the experience is exhilarating. You feel the impact of every punch, see every writhing facial contortion, hear the thud of leather hitting flesh and flesh hitting canvas.

You also hear the roars of the crowd when their favored fighter throws (forget about landing) a punch. You hear the conversations and mutterings of those around you about how the fight is going. You miss stretches of action when the referee is in your sightline, or when the boxers are working against the far ropes, or when one fighter has his back to you and the other boxer is completely obscured.

The judges who regularly score fights ringside experience the same visceral immersion, hear the same roars from the crowd, and encounter the same visual obstructions. While they are trained and paid to overcome such obstacles and provide an objective scoring account of each round, expecting perfection from human beings in a chaotic atmosphere is like expecting the apocalypse to arrive because some octogenarian jagon made up some bible math and said it would—it’s hopelessly naïve.

Therefore, I believe the time has come to take judges away from the ring, to embrace technology, and to begin scoring fights from high definition television monitors.

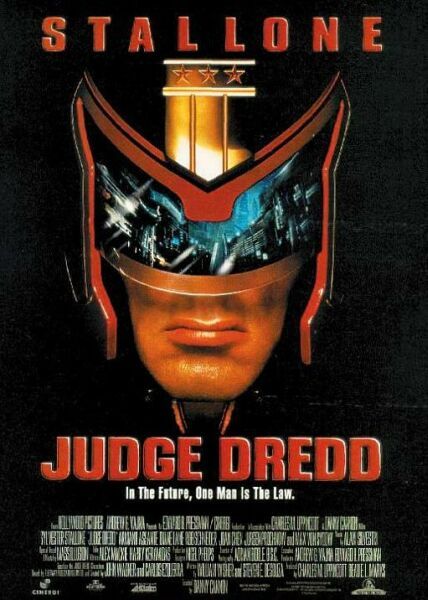

(I would also fully support Judge Dredd scoring every major fight going forward.)

It’s simple, really — you take the three judges who usually sit ringside, move them to a room in the arena away from the fight area (to minimize the impact of crowd noise), and set up a high definition monitor for each to watch the fight on, with a video feed but no audio.

The biggest hurdle overcome by television monitors is obstruction. There will still be moments in the fight in which the referee will block the view of the action, or when an exchange is difficult to see because of the positioning of the boxers, but with multiple cameras capturing the best view at any given moment (as they do now), the visual obstructions will be minimized exponentially. Now that high definition technology is widespread, the clarity of televised images makes the incorporation of television monitors into boxing judging that much more logical.

The other major hurdle overcome would be the impact of the atmosphere on officials. No matter how truly and honestly a judge professes to be neutral, the subconscious impact of thousands of people screaming in unison when one fighter throws a punch and reacting with stony silence when the other lands a conversation is impossible to know and equally impossible to overestimate. Were the judges who scored Pernell Whitaker-Julio Cesar Chavez a draw blind, corrupt, or just subconsciously influenced by 56,000-plus screaming Chavez fans who roared with every punch he threw? Was the judging in the first Paulie Malignaggi-Juan Diaz fight corrupt, or were the officials influenced by the Texas crowd and its support of Diaz? Were the judges for the first Bernard Hopkins-Jean Pascal fight at the raucous Pepsi Coliseum in Quebec City really able to ignore the crowd, or did the crowd’s enthusiasm sway their opinion in another disputed draw?

Of course, boxing embraces change like mysophobes embrace crackheads with bleeding lesions, so I don’t expect ringside judges to disappear tomorrow. But the time is ripe for a re-evaluation of a scoring system which has gone unchanged for decades — a scoring system that nobody ever seems happy with (when is the last time you heard a fighter or read a boxing writer praising a judge’s performance?); a scoring system that ultimately decides the fates of hardworking pugilists, their financial and physical futures and their place in history.

(Or, we could just ask Judge Reinhold. Mock trial!)