With Bernard Hopkins returning to arms next weekend, Andrew Harrison looks back at the Philadelphian’s middleweight championship reign — a fantastic run but a record breaking one?

A great bumper sticker once noted that during a time of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act. And while Big Brother should not concern itself with murmurings of a rebellion just yet, it’s time to set fire to our bras, brahs. Insurrection is in the breeze, with a picket line forming at the gates of boxing fallacy. Specifically, it opposes the notion that Bernard Hopkins holds the world championship defence record at middleweight, after he was reckoned to have eclipsed the imperious Carlos Monzon in 2002.

In April 2005, William Dettloff added weight to this theory after he penned a Ring Magazine article suggesting boxing’s greatest world title tenures. There, perched one spot behind the legendary Joe Louis, but nestled ahead of Monzon and other luminaries such as Henry Armstrong and Archie Moore, sits Hopkins. Curiously, Hopkins attained his lofty position despite the fact he owned only a portion of the full championship for the majority of his term. Odder still, there was no mention of other, similarly long-reigning alphabet titlists such as Dariusz Michalczewski, Chris Eubank, Orlando Canizales and Virgil Hill — not even in the “next 10” section.

Ring Magazine’s website recently published a Lee Groves-written piece that zeroes in specifically on the “greatest middleweight champions of all time.” Hopkins is afforded top spot in a somewhat surprising top 10, once again ahead of Monzon – so what gives?

Hopkins picked up a slice of the middleweight pie in April 1995 (IBF version) after pounding out a 7th round TKO over Segundo Mercado in Landover, Maryland. It was Bernard’s third crack at winning the belt after coming up short in two previous tries. Roy Jones, Jr., the Floridian thoroughbred, turned back Hopkins in the summer of ’93 and, after Jones plumped to vacate in order to hunt down the unbeaten James Toney at 168 lbs., Mercado held Hopkins to a stalemate, in a bout to contest the vacant title in the Ruminahui Coliseum, Quito, Ecuador.

A world titlist at long last (after the rematch), Hopkins proceeded upon a dogged occupancy, one which spanned a decade and was curtailed only a few months yon side of the Ring Magazine piece. Despite this, Hopkins wasn’t ever considered as divisional chief until his mastering of former welterweight wrecking machine Felix “Tito” Trinidad in September 2001. Monzon on the other hand was crowned king from the get-go, after disarming Slovenian-born Nino Benvenuti in November 1970 — which is precisely the point these metaphorical placards and banners are attempting to make.

Sharing world championship status with a variety of peers doesn’t necessarily preclude a man from being proclaimed as “The Man,” of course, so preposterous are the rulings of boxing’s various alphabet organisations (with middleweight kingpin Sergio Martinez being a contemporary case in point). A look back, though, negates any suggestion that corporate whimsy had a bearing upon Hopkins’s claims.

Esteemed British boxing magazine Boxing Monthly ranked both he and Mercado only fifth and sixth at the weight respectively prior to their return, with Hopkins only rising to second (behind Argentinean Jorge Castro) after dealing with the Ecuadorian at the second time of asking. In actual fact, had Ireland’s Steve Collins and Illinois knockout artist Gerald McClellan not invaded super middleweight only months prior, Hopkins may not even have cracked the BM top three. Stateside, Hopkins could only manage a top three berth with KO Magazine, who preferred the claims of both Castro and Texan southpaw Quincy Taylor. Ring Magazine meanwhile appointed Taylor as their middleweight of the year. Unlike Monzon, Hopkins clearly wasn’t class leader.

Within a year of becoming champion, Monzon had stamped his authority on the division with stoppage victories over Benvenuti (again) and former two-weight world champion (at both welterweight and middleweight) Emile Griffith. Throughout his near seven-year run, “Escopeta” (shotgun) would engage in a total of five non-title affairs against flimsy opposition that, had the governing bodies seen fit to deem them worthy, would have extended his record to an incredible 19 defences.

Fast-forward 20 years and that level of quality control had long since evaporated. Hopkins began racking up alphabet defences against the likes of Steve Frank, Joe Lipsey and Bo James. Both Castro and Taylor had been upset by this point (at the hands of the Japanese Shinji Takehara and Washington’s Keith Holmes respectively) leaving Hopkins, marking time and little more, top of the heap. Yet still he wasn’t champion outright. Hopkins needed Don King in order to achieve that goal.

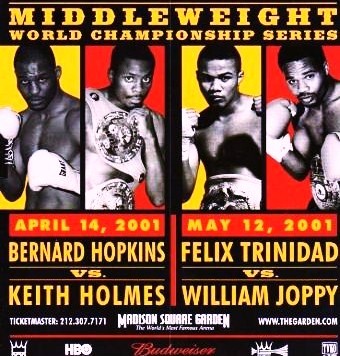

Puerto Rican puncher Trinidad had conquered both the welterweight and junior middleweight classes and in 2001 he set his crosshair on a more glamorous crown. King shifted his promotional heft behind a middleweight unification tournament, one that would pair Trinidad (as the draw) and three 160 pound belt holders against one another, in a bid to coronate the first universally recognised middleweight champion since Sugar Ray Leonard in 1987.

Holmes was coerced into putting up his WBC strap against Hopkins’s IBF version, while in the other semi-final “Tito” was unleashed upon the WBA titlist, William Joppy. Hopkins cowed and then brutalized Holmes over 12 one-sided rounds before Trinidad justified his odds as pre-tournament favourite with a chilling five round demolition of Joppy – a man Hopkins himself had rather presumptuously compared to the aforementioned Leonard. All three “major” world titles were united at Madison Square Garden that autumn, just weeks after terrorists had devastated New York (which postponed the fight from its original date). When finally they met, Hopkins delivered his greatest performance, halting Trinidad in the final round. Hopkins was the middleweight boss at last and America finally embraced this most obstinate outlaw.

Hopkins successfully defended the full championship six times in all, against fair-to-middling opposition, before Jermain Taylor, an unbeaten former Olympian from Arkansas, derailed the master craftsman twice in 2005. Those defeats mattered little. Any number of media outfits, including influential U.S. broadcaster HBO, had already declared Hopkins the owner of a historical record and, whilst it is true he had defended one third of the championship a total of 20 times in all before Taylor disrupted him, what he hadn’t managed to do was match Monzon. Not that you’d have known it.

Hopkins appeared then to be afforded some sort of retrospective benefit of the doubt, as if finally becoming champion proved he was the champ all along. This is a pointedly different scenario to the champion who finds himself suddenly stripped of his titles, after the various organisations that once bejewelled him in harmony, subsequently elect to head off in separate directions (Monzon suffered just such a fate himself, when in 1974 the WBC retracted their award, after he failed to defend against Colombian Rodrigo Valdez; Monzon would later best Valdez twice before retiring in 1977). So, did the fact that Hopkins wound up a unified champ skew the reality that for the majority of his era, he hadn’t been? Was it an oversight, or overcompensation for him being overlooked?

Welsh whirlwind Joe Calzaghe, who would eventually oppose and then dethrone Hopkins at light heavyweight, achieved similar statistics to “The Executioner.” Calzaghe managed to guard his WBO super middleweight title some 21 times over a comparable period and, like Hopkins, skirted the sport’s margins for many years. He, too, came in from the cold late into his reign, after winning a unification bout from long odds against an unbeaten potential star. The Newbridge tempest blossomed too late to make Dettloff’s list, yet is it likely that the unbeaten swarmer’s largely insipid sovereignty would have been rated one of history’s finest, despite it paralleling eerily with Hopkins’s own, give or take a few letters?

Ragging on a man’s achievements, especially those earned through back-breaking hard work, will always appear questionable. Yet further perpetuation of the myth that Bernard Hopkins surpassed Carlos Monzon commits a comparable sin. For unless some semblance of standards are maintained, unless championships are identified separately from mere titles, how soon will it be before some diamond, interim or similarly watered down denomination of a champion is adjudged to have trumped even Hopkins?